If in 2023 the works of renowned literary authors such as Miguel Hernández or Virginia Woolf entered the public domain, 2024 brings the extinction of the exploitation rights over one of the most famous animated characters in the world, Mickey Mouse, although with important nuances.

If in 2023 the works of renowned literary authors such as Miguel Hernández or Virginia Woolf entered the public domain, 2024 brings the extinction of the exploitation rights over one of the most famous animated characters in the world, Mickey Mouse, although with important nuances.

One of the fundamental features of copyright is its temporality, which means that they are not a property with perpetual nature, so that once the exploitation rights are extinguished the works can be used by anyone as long as the authorship and integrity of the work are respected. The duration of copyright is set out in our Intellectual Property Law which, as a general rule, establishes that copyright shall last for the life of the author plus 70 years after his/her death, with the exception of those authors who died before the 7th December 1987, which shall last for 80 years post mortem auctoris.

Some of the works which enter the public domain this year are those of authors such as Carlos Arniches (member of the 98 generation), Alfonso Nadal (who translated to Spanish works of Dostoevsky and Hans Christian Andersen) or Eulalia Abaitua (pioneer of the Basque photography). But, without a doubt, if somebody has grabbed the spotlight the last few weeks that has to be Mickey Mouse, since Disney’s famous mouse has entered the public domain this 2024. However, does this mean that Disney has lost control over its flagship? Far from it.

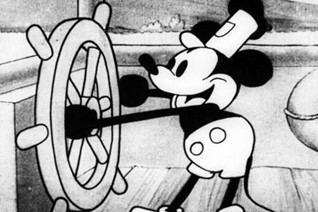

Firstly, it should be pointed out that the rights to Mickey Mouse which expire are not those of the version we can find today, but those of his first design, which appeared in the animation of the famous Steamboat Willie, still in black and white. In other words, the Mickey character as such cannot be used freely, but only that initial version. It should be borne in mind that copyright does not protect a fictional character in the abstract, but rather those representations and expressions in certain works, such as books or films. Therefore, in view of the evolution of the Mickey Mouse character and his different designs, there are several Mickeys with their respective terms of protection as they are independent works, each one with its own original design.

On the other hand, it is important to note that the protection of fictional characters like Mickey is not limited to copyright, as trademark law represents a fundamental tool for their commercial exploitation, as well as for extending the protection of these characters over time. By registering a trademark it is possible to protect both the name of the character and its design, with the clear benefit for the owners that there is no time limit for exercising trademark rights, since it is only necessary to renew the registration (at the SPTO and EUIPO every 10 years) and to keep the trademark in use.

This transfer of copyright to the field of trademark law, although covered by the configuration of our legal system, implies directly bypassing one of the essential principles of copyright as temporality. Although it could be argued that the principle of speciality that governs our trademark system limits the scope of protection for these characters as trademarks, we cannot forget that in many cases these characters enjoy widespread fame among consumers, so that the application of the regime envisaged for well-known trademarks cannot be ruled out, with the consequent breach of the principle of speciality.

This being the case, with works that will undoubtedly enter the public domain, one must be aware of the existence of trademark rights that may protect these creations, otherwise it is very easy to incur trademark infringement under the premise of using a work in the public domain. It will be interesting to see how the rights management of such fictional characters develop over the next decade, as well as the uses made of them by authors around the globe or their interaction with AIs.

Jorge Díaz Rodríguez